Why are office buildings in CBDs continuing to recover faster than suburban properties? One fundamental driver is the difference in post-recession hiring patterns between large and small firms.

Typically, when the office market begins to recover suburban submarkets recover sooner than their CBD counterparts. However, during the recent phase of economic recovery, the reverse has been true—CBD submarkets began recovering sooner with suburban submarkets following suit. This is a trend we identified back in late 2010, when the office market had yet to show consistent signs of a recovery.

One key factor in understanding this reversal is the link between the labor market and office submarkets. Generally, a company’s location decision is a function of size.

Smaller firms (500 employees or less) tend to locate in suburban office submarkets. These firms tend to be more entrepreneurial, often younger, and less established. Therefore, they focus on having a viable business and seek the cheapest office space that suits their needs, usually located in the suburbs.

Larger firms (greater than 500 employees) tend to be more established and locate in the CBD submarkets. The already have a viable business and they desire an address that conveys an image of success. Moreover, these firms tend to co-locate with other firms in their industry to capitalize on economies of scale by sharing input providers, a labor pool, and information.

During economic recoveries, small firms are born out of the “creative destruction” of recessions. They are created by people who lost their jobs, people who cannot find employment, or people that have an idea for how to do something better. They capitalize on the lower costs of doing business during weaker economic periods like rents and wages. These firms tend to lead the labor market in hiring during recovery periods.

Small firms have a concurrent need for employees to run their business and hire accordingly. Larger firms typically adapt to poor economic conditions by squeezing productivity out of their workers. They hire but only when the need arises. Therefore, during the first couple of years of labor market recovery, more jobs are created by smaller firms. Thereafter, as the recovery becomes entrenched, large firms have increased confidence and opportunities and they hire in greater numbers than smaller firms that have already built up their organization. The impact of these tendencies is that suburban office submarkets tend to recover sooner than CBD office submarkets.

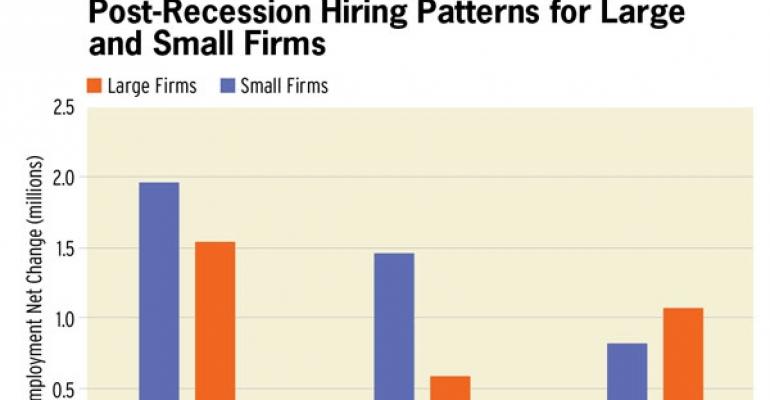

During the economic recovery of the early 1990s we can see that during the first two years of the labor market recovery in 1992 and 1993, hiring by small companies outpaced hiring of large companies—small firms created roughly 1.95 million jobs while large firms created 1.52 million jobs. Consequently, the changes in suburban and CBD vacancy rates reflect this—during this time suburban vacancy fell by 355 basis points while CBD vacancy fell by 6 basis points.

Over the next seven calendar years before the economy entered another recession, the trends reversed. Large companies generated more jobs than small companies in each of those seven calendar years. From 1994 through 2000, large firms created 11.23 million jobs while small firms created 7.36 million jobs. Correspondingly, the CBD vacancy rate during that period declined by 1140 basis points. In contrast, the suburban vacancy rate declined by 797 basis points.

During the economic recovery of the early 2000s, similar trends appear. During 2003 and 2004 as the labor market began to recover, hiring by small firms of 1.44 million jobs outpaced hiring by large firms of 592,000 jobs. During this period suburban vacancy fell by 35 basis points while CBD vacancy rose by 130 basis points. Over the next three calendar years before the economy went into recession in 2008, the trend reversed.

Once again, large companies generated more jobs than small companies in each of those three calendar years as large firms created 3.09 million jobs while small firms created 1.89 million jobs. As a result, the CBD vacancy rate declined by 476 basis points while the suburban vacancy rate declined by 363 basis points.

However, in the current recovery, this typical trend has not occurred.

Small firms have been lagging their larger brethren in hiring for a number of reasons, one of the most prominent being the lack of funds necessary to start and run a small business. In the wake of the credit crisis, liquidity remains tight and the traditional sources of financing for small firms, such as credit cards and home equity loans, were either closed or infeasible.

Consequently, better-funded large companies have been leading the charge. Although quarterly data is only available through the first quarter of 2011, since the advent of the labor market recovery in the first quarter of 2010, large companies have created 1.06 million jobs while small companies have created 823,000 jobs. Over this internal, CBD vacancy is virtually unchanged, rising by just one basis point while suburban vacancy has increased 89 basis points.

During 2011 net absorption in suburban submarkets began to outpace net absorption in CBD submarkets. This intimates stronger hiring by smaller firms during that period.

However, it should be noted that net absorption in the suburban submarkets is being driven by a small number of industries in specific metro areas. For example, energy and technology firms, which have been performed well over the last few years, have driven net absorption in a handful of markets—roughly one-third of the positive net absorption (excluding metro areas with negative net absorption) is occurring in energy—and technology-oriented metro areas.

While it is true that some successful small firms experience sufficient growth and become big firms, leaving one category and joining another, this does not occur in sufficient enough quantities to skew the results. This office market recovery is different because the composition of job creation in this recovery has thus far been different than in previous cycles.

Victor Calanog is head of research and economics, and Ryan Severino is senior economist, for New York-based research firm Reis.