The U.S. is having difficulty returning to prosperity because of several major dilemmas. In the long run, we need to adopt actions that slash our rising deficit and debts, but those actions are opposed to the behavior we need to implement right now to overcome high unemployment and low growth. This dilemma, plus disagreement in Congress about which way to go, has produced policy paralysis.

One baffling dilemma facing us is our need to reduce our consumption spending in the long run, in the face of retailers’ and other employers’ need for more consumption now to stimulate their growth and hire more workers.

During the 1990s, total consumer spending amounted to 62 percent of gross domestic product. In the 2000s, the share rose to 71 percent.

We were living beyond our means by using our homes as banks and importing low-cost items from China. This is still a major cause of our trade deficit. We need to reduce our consumption and increase our savings to end excessive imports. But cutting consumption now will worsen the prosperity of most retailers and manufacturers by causing further rising unemployment.

Moreover, Republicans in Washington, D.C. strongly oppose any attempts to stimulate the economy through more government spending. Also, they refuse to increase government revenues through higher taxes on the wealthy. Yet in the 1990s President Clinton raised tax rates on the wealthy from 27 percent to 40 percent without slowing down a strong job-creating boom.

A second dilemma concerns what to do about the banks considered “too big to fail” that received bail-outs from the federal government. Almost no top officials in those banks suffered serious personal losses in spite of the giant injuries they inflicted on everyone else. None have been indicted for fraud or subjected to large fines, while millions holding assets that the banks sold them have experienced huge losses.

No wonder most Americans are outraged by big banks and Wall Street!

Those groups prosper by borrowing at 1 percent from the Federal Reserve and investing at 5 percent in Treasury bonds, paying themselves huge bonuses, yet they are not lending much to borrowers needing capital. If we leave these bankers without penalties for forcing the government to bail them out, they will take excessive risks once again, knowing the government will save them.

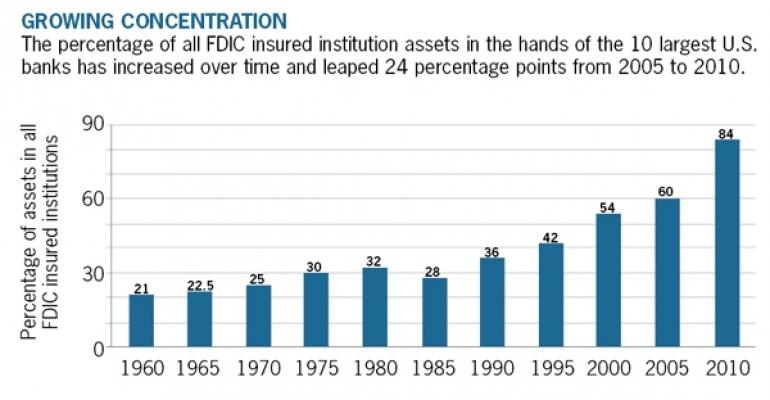

Today, the largest 10 U.S. banks contain 84 percent of all assets held by all 7,830 institutions insured by the FDIC; the other 99.9 percent of banks hold only 16 percent! In 1995, before the Glass-Steagall Act was repealed, the top 10 banks held only 42 percent—half as much as today.

The Obama administration, up to now heavily staffed by former Wall Street executives, has refused to subject these big banks to any legal attacks or penalties, or to try breaking them up. True, the FDIC is seeking to force big banks to develop rapid liquidation plans. But I am not convinced this administration is willing to really reduce the incentives for big banks to repeat their recent flagrant risk-taking.

Another dilemma exists in housing markets due to the large numbers of homes being foreclosed, mainly because many home values fell far below the values of owners’ mortgages. Housing starts plunged 71 percent from their high of over 2 million in 2005 to approximately 600,000 this year. Foreclosure filings are still hovering around 2 to 3 million per year.

The overhang of foreclosed and unsold homes in the nation’s housing markets, plus continuing high construction unemployment, are preventing any speedy return to housing prosperity. The government’s attempts to encourage housing recovery are not working because succeeding would require permitting many home owners to take major write-downs in their mortgage principles and payments. But the mortgage holders—including many banks—refuse to take big “haircuts,” they would rather go through foreclosure, hoping for a better deal.

Another real estate dilemma concerns the large debts that are outstanding on many commercial properties. Most banks are reluctant to extend enough credit to permit borrowers to pay off the loans they used to finance commercial properties, since values of those properties have fallen sharply.

Therefore, many lenders “extend and pretend” that those loans can be more fully repaid in the future. Yet the federal government can do little because the amounts of money involved are so large. Some deals are returning in commercial markets, but a majority of the excessive loans made in the early 2000s are still out there, not fully refinanced.

These and other dilemmas complicate the possible ways of getting our economy out of this still painful recession. It is unclear how we can act strongly enough in the short run to get us back into prosperity, yet also reduce our spending in the long run to attack our burgeoning debt. The policy gridlock in Washington is no help. It is going to be several more hard years before we can overcome these dilemmas.

Tony Downs, is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.