The amount of distressed commercial real estate properties in the U.S. has reached a record $180 billion, according to a new report by New York-based research firm Real Capital Analytics. The distress reaches across all property types, with the greatest amount plaguing retail assets, the report shows.

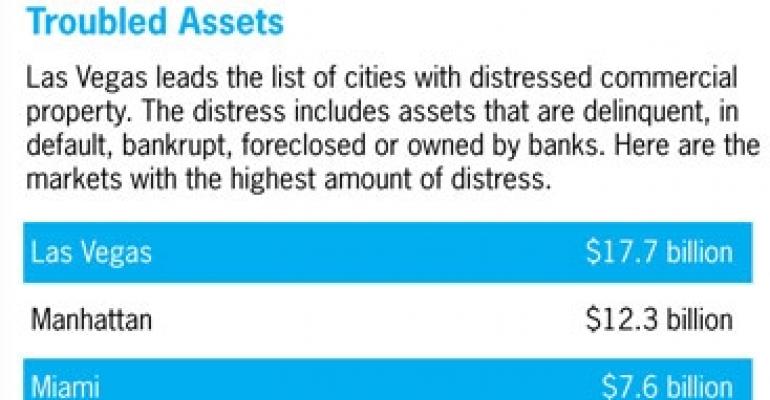

By far, the market with the highest dollar value of troubled assets is Las Vegas, with $17.7 billion of properties that are delinquent, in default, bankrupt, foreclosed or otherwise owned by lenders.

Manhattan had the second-highest amount of troubled properties as of November, $12.3 billion, followed by Miami, with $7.6 billion and Los Angeles, $7.1 billion.

“The distress is formidable,” says Dan Fasulo, managing director of Real Capital Analytics. Most of the financial problems accumulated between September 2008, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, and November 2009, he says. “Before 2008 there was no material distress in commercial real estate — period. It was just a normal market. This isn’t something you can compare with other periods. This is new for everybody.”

Unfortunately, the pace of the distress process is not slowing, says Fasulo. “I think we’ll continue to see more distress come to market well into 2010. I like to think we might hit the apex in the middle of 2010 and then start working our way down.”

As the flow of distressed properties continues unabated, resolution of the problem has been slow in taking effect. Just 10% or $18 billion of the distress has been resolved, according to the research firm.

Recent federal regulation is likely to restrict defaults among commercial properties with continuing cash flow by encouraging loan extensions and restructurings. But when it comes to properties without cash flow, such as failed developments or vacant buildings, lenders will have little alternative but to foreclose, according to the report.

“Those are assets that have no chance of recovering their full value in the short term. In those situations lenders just aren’t in a position to carry those assets for a long time. Many are [real estate owned by banks] already, but even more working are their way through the process,” says Fasulo.

Retail was the hardest-hit sector with $37.5 billion in troubled assets. Hotels were second with $32 billion, followed by office, $28.2 billion, and apartments, $27.9 billion. The industrial sector had just $5 billion in distressed assets.

Much of the distressed retail property lies in U.S. suburbs, where new residential developments were planned but never completed, because of the recession and credit crisis. “I’ll never forget driving around the loop in Vegas. There’s a brand new retail center on the desert next to the highway,” near an abandoned housing development. “It’s all plotted out for new houses. Obviously they’re not going to build the houses now,” says Fasulo.

Industrial properties fared better than other types, and are expected to remain strong into next year. “It’s not the sexiest sector. It never got over-levered the way some property classes did,” notes Fasulo. Another plus: the warehouse industry is upgrading the market with new, high-tech facilities, he says.

Investors voice frustration

Despite the high level of distressed properties, on the demand side many investors are aggravated. “I get upset calls from investors almost every day, frustrated that they can’t find anything to buy. It sounds so counterintuitive,” says Fasulo.

But a lot of the sale action is taking place on the debt side. In this difficult economic climate many properties don’t come to market in the usual way, with the help of brokers. “A lot of investors are trying to sneak in and buy the first mortgage or mezzanine debt to take control of the property that way instead of participating in a public auction,” notes Fasulo.

For the most part, investors who expected to see prime retail or office properties trotted to the market at huge discounts have been disappointed. Instead, the investors have had to become highly creative at ferreting out attractive distressed properties with bargain prices.

Because the deals have been hard to find and often have entailed “back door” access to lenders and other sources, requiring thorough knowledge of a market and connections, many investors have turned to their own local markets to find deals, says Fasulo.

For example, the recent auction of the trophy W Hotel in New York took place at an attorney’s office. There’s no way an investor sitting at a computer in Los Angeles could gain proper entrée to a deal like that, says Fasulo. That’s why so many investors now are taking a closer look at available deals in their own backyards.