As commercial real estate distress continues to mount, dozens of retail real estate firms, including brokers, third-party managers and developers, are jockeying to get a piece of the business. But the assignments so far have been coming in dribs and drabs, not quite the tsunami of opportunities many of these firms had been expecting.

A combination of government recommendations to lenders to amend troubled loans whenever possible and banks’ inability or unwillingness to absorb potential losses, has led to inaction on assets with underwater loans.

That’s starting to thaw a bit, however, says Greg Maloney, CEO and president with Jones Lang LaSalle Retail, an Atlanta-based third-party property manager. Jones Lang LaSalle currently has 48 assets under receivership, including a mix of office buildings, retail centers and multifamily properties. That’s up from 10 properties at the end of 2008.

Meanwhile, by the end of fourth quarter last year, CB Richard Ellis had 20 million sq. ft. of properties under receivership in the U.S. and was marketing $5 billion in distressed assets for sale, up from $3 billion in the third quarter.

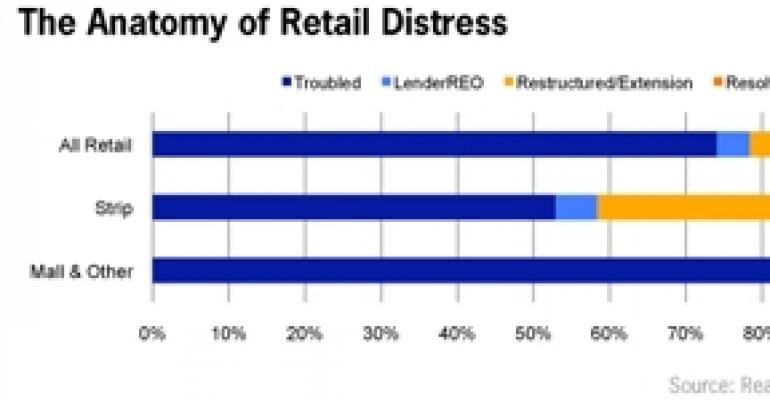

The numbers still seem small compared with the total level of distress in the market. At the beginning of February, New York-based research firm Real Capital Analytics identified $43 billion in retail assets in default, foreclosure or bankruptcy across all lender types. To date, only $1.1 billion of this distress has been resolved. But Maloney expects that lenders will begin putting more properties into foreclosure and receivership in the run-up to the May ICSC RECon conference in Las Vegas.

“Lenders are starting to divide [traditional loans] into different categories — these are the ones where we want to work with the borrower, here are the ones we want to foreclose on, here are the ones we want to put into receivership,” Maloney says. “I don’t think you are going to see a tsunami by any means, but I think it will continue to pick up.”

Receivers are getting few assignments for regional mall properties and larger shopping centers. Most receivership assignments being placed in the retail sector are on smaller properties including single-tenant assets and strip centers. The debt on these properties tends to be whole loans originated and held on the books of local and regional banks.

Those banks didn’t have the lending capacity to finance larger power centers or regional malls. The loans for those assets instead were more commonly financed through complex transactions featuring senior lenders and several mezzanine lenders with some or all of that debt ending up getting packaged into commercial mortgage-backed securities, says Samuel Delisi, senior managing director of asset services with CB Richard Ellis.

In that case, after the borrower defaults, the loan has to make its way through a circle of different lenders before it can be put into receivership, prolonging the period between the onset of distress and resolution. Larger assets will start going into receivership in much greater volume later this year and through 2011, Delisi predicts.

Overall, he estimates that today, CB Richard Ellis assumes receivership services for between 300,000 sq. ft. and 500,000 sq. ft. of retail properties on a monthly basis — primarily single-tenant assets and strip centers. The company is serving as receiver for 150 assets nationally, about a quarter of them retail.

Nevertheless, receivers across the board report that they are finally starting to put assets on the market and close some transactions. So far, most of the properties being traded in the distressed arena are smaller centers, valued under $10 million.

But as time goes by and an increasing number of loans come due and lenders are forced to accept reality, investors will become more aggressive in snapping up properties, according to Maloney. Right now, most prospective buyers remain uncomfortable with the level of risk they are expected to take on.

So far the distressed properties that have come to market generally have serious problems at the property level. These assets may be developments still under construction and require additional work, or have extremely low occupancy levels. A new owner can be required to lease up a significant portion of the property, or complete the development when it’s difficult to secure new tenants and it is unknown when the market will turn. In addition, many of these sales are done on an all-cash basis, so the buyer is taking on more of the risk directly.

“Personally, I think there has to be a realization of what it’s going to take to move the asset and the banks are going to have to make it a little bit more attractive to the investor,” Maloney says. “Right now, it’s little reward for a lot of risk and that’s why things aren’t moving.”