As the summer comes to a close, CMBS players are breathing a sigh of relief.

Although the industry has experienced some turbulence this year, it was lucky enough to avoid a crash like it went through last summer due to the European debt crisis and the drama surrounding the U.S. debt ceiling. The CMBS market has finally stabilized, experts say, leaving lenders, borrowers and investors quite content with current conditions.

“It’s night and day compared to this time last year,” says Doug Mazer, co-head of Wells Fargo’s CMBS lending group. “Right now we’re in a period of relative stability. The last two CMBS pools in the market were oversubscribed, and a lot of that has to do with the fact that we’re in a period of relative calm.”

Perhaps the biggest issue the sector is facing is tied to perception. For many borrowers, a conduit loan is acceptable, but not preferred—they would much rather have a loan from a portfolio lender because they’re aware of the difficulties inherent in conduit loans.

“There’s no question that some borrowers have experienced legacy CMBS issues or they’ve heard stories about it,” Mazer says. “That perception can be an issue. But, when borrowers need attractive terms that they can’t get from a portfolio lender, they migrate to CMBS financing.”

Because borrowers are aware of the challenges created by conduit loans, they’re borrowing smarter, says Jimmy Board, a senior vice president in Jones Lang LaSalle’s Houston office.

For example, borrowers and lenders are working together to create loan documents that try to incorporate more flexible language regarding the property’s business strategy and plan.

“Originators understand that they can’t do much to protect borrowers after the deal is securitized, and the only way to protect them is to include borrower-friendly language—something that was missing in the deals that were done in the 2005 to 2007 period,” Board notes. “CMBS received such negative buzz because of special servicing issues. CMBS shops realize that borrowers are skeptical so they’re paying more attention and trying to do more things to protect borrowers so they can win back their confidence and their business.”

Volume projections

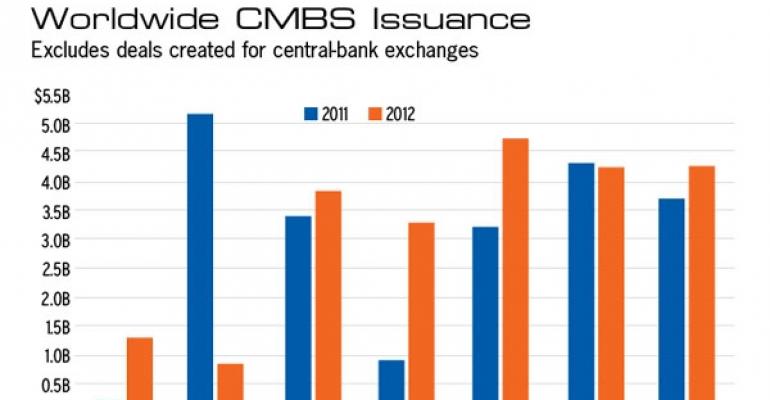

There are other ways in which the CMBS sector continues to move slowly. CMBS origination volume for this year is forecast to reach roughly $33 billion—on par with 2011’s total of $32.9 billion. Many industry experts say that number is both disappointing and unimpressive. Not only does it fall short of earlier forecasts of $45 billion, it represents only a small fraction of the $207 billion issued in 2007, according to Trepp LLC, a New York City-based firm that tracks CMBS performance.

However, comparisons involving issuance volume can be slightly misleading, asserts Gerard Sansosti, an executive managing director in HFF L.P.’s Pittsburgh office who heads up the firm’s debt platform. He explains that some of the CMBS deals that were securitized in 2011 and contributed to last year’s total were actually originated in 2010. Since conduit origination during the second half of 2011 was almost non-existent, securitization volume in early 2012 was miniscule.

“I’d say that 2012 origination has been pretty steady, and a lot more players are in the market,” Sansosti says, estimating that there are about 25 conduit lenders in the marketplace today.

Of course, many of the lenders that were active during the CMBS heyday are gone—Bear Stearns and Lehman Bros., for example. However, most lenders that suspended their conduit lending programs during the credit crisis are back in the game, along with some new faces. JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs and RBS were among the first to return to the market, and Wachovia is now lending under the Wells Fargo umbrella.

New York City-based Ladder Capital rolled out a conduit program, as well as Cantor Fitzgerald, which hired a number of conduit professionals from Credit Suisse’s downsized CMBS shop, says Constantine Scurtis, CEO of SL Capital, a correspondent lender of Cantor Fitzgerald Commercial Real Estate (CCRE). The firm now has more than 100 people working on conduit lending and is on track to close $7 billion in CMBS this year.

Unfortunately, the CMBS market likely is facing another 12 to 18 months of malaise, contends Tom Fink, senior vice president at Trepp. The U.S. presidential election is weighing on the overall economy, as is the ongoing debt situation in Europe. Together, the uncertainty is undermining the recovery of the CMBS market. Moreover, many of the proposed rules and regulations that were created to reform CMBS have yet to be enacted.

Investment demand

Most important, however, is the sluggish investment sales environment, Mazer notes. Although trades are occurring more frequently, the activity is still somewhat muted, which is negatively influencing conduit lending volume. “We’re just not seeing acquisitions like we did before,” he explains. “The acquisition market is a big piece that would need to come back before we would see larger volumes.”

In the meantime, however, borrowers that are looking for CMBS loans can find them, and at good rates, too, now that CMBS investors have gotten comfortable with the risk profile these investments offer today, Scurtis says.

“It’s the B-piece buyers that determine demand and pricing, and right now, there’s a lot of demand from them,” he notes. “It’s nothing like the past, of course, but there’s much more demand than people realize for well-underwritten CMBS debt. Yes, CMBS investors were burned, but when they have billions of dollars to put out, and they start analyzing the options, CMBS is a very compelling story once again. They’re looking at bonds supported by loans with reset values on quality assets with stable incomes.”

The low yield environment is pushing investors toward CMBS, even those that are risk-averse. “It has been a slow build up back to investor confidence in the product,” Mazer says. “Market participants know what has happened and are mindful of the risks.”

However, there are a number of things that have allowed investors to get comfortable with CMBS again. “There are more regulations, more moderate leverage and more transparency,” he points out. “The product itself is a safer investment than it was at the 2007 peak.”

Mazer also suggests that CMBS yields are relatively attractive compared to other investments. “There are just not a lot of places for investors to put their money to get relatively high yields with relatively safe investments,” he explains. In fact, bond buyers who invest in B-piece CMBS are achieving yields of 20 percent or more, according to experts.

Scurtis says CCRE has involved B-piece buyers early in the origination process so they clearly understand the risk. “It’s almost like they’re part of our credit committee,” he explains. “We’re showing them everything before closing—almost like getting pre-approval from them because we don’t want to risk any kick-outs.”

The message from these B-piece buyers is clear, Scrutis says: “They don’t want any fat in the underwriting—the loans aren’t based on future cash flows, but on existing rents. We’re even writing down rents if we think they’re higher than market, and we’re including rent rollovers. They’re not interested unless the loans are for stable, quality assets.”

Terms have changed

Unlike the heyday when conduit lenders competed head-to-head with portfolio lenders and won deals with higher proceeds and lower rates, conduit lenders today are winning deals primarily on proceeds, says Board.

“Rates between conduit and portfolio loans are probably the tightest we’ve ever seen—35 to 50 basis points, but it’s the leverage that makes the difference for borrowers,” he adds. “If a borrower needs leverage to hit their investment returns, they’re going to look for the most proceeds they can get.”

On average, portfolio lenders are willing to make a non-recourse loan up to 65 percent LTV, while CMBS lenders are up to 75 percent. While that LTV is still below the 90 and 95 percent LTV seen prior to the credit crisis, it’s enough of a difference to create a competitive situation.

“If I am a borrower and I need to be over 65 percent leverage with non-recourse, there are very few alternatives other than CMBS and mortgage REITs, whose pricing is nowhere near CMBS,” Sansosti says.

Rate floors, instituted at 4 percent by portfolio lenders because interest rates are so low, have allowed conduits to get closer in pricing to portfolio lenders. Without those floors, rates on portfolio loans would be well under 4 percent, Sansosti says. “The floors have allowed conduit lenders to narrow the gap,” he explains, pointing out that earlier this year conduit loans were priced at roughly 6.5 percent. Now they’re in the 4 percent range as well.

Fink says that lenders aren’t basing their rates on today’s interest rates, either. “We’re seeing conduit lenders trying to write loans today assuming interest rates will double or triple so they won’t get stuck,” he notes.

Filling in the geographic gaps

Higher leverage aside, conduit lenders continue to have a hard time competing on institutional quality assets in major markets. “Portfolio lenders today are able to attract the highest quality properties—if they really want a loan, they can get it,” Fink points out.

Fink notes that portfolio lenders command a larger share of the marketplace today than they did in the heyday of CMBS issuance from 2003 to 2007. Life insurance companies, for example, have increased their allocation to real estate, so they continue to be very active in commercial real estate lending.

That’s why conduit lenders are actively seeking deals in secondary and tertiary markets. Because they’re willing to venture into markets that portfolio lenders ignore—like Nashville, Tenn. and Detroit, for example—they can satisfy investor demand for quality, stable assets without competing on price or proceeds. “Portfolio lenders discriminate geographically, but CMBS doesn’t,” Sansosti points out.

Indeed, Fink estimates that CMBS reaches into two-thirds of the MSAs around the country, while portfolio lenders limit themselves to the top 25. “CMBS fills the cracks—it’s always had an ability to reach deeper,” he says.

And CMBS not only goes “deeper,” it also goes bigger, Sansosti points out. “There are only a few portfolio lenders that can do deals that are $100 million or larger, and most of them don’t want to take on that much risk with one deal. As a borrower, you’re better off going the CMBS route.”

Mazer says Wells Fargo is focused on high-quality, trophy assets, and he expects that more super-sized deals will end up with CMBS loans in the future. “It’s not just leverage that might steer a borrower our way. The overall size of a loan may steer a deal to CMBS because portfolio lenders have limits on their loan sizes,” he explains.