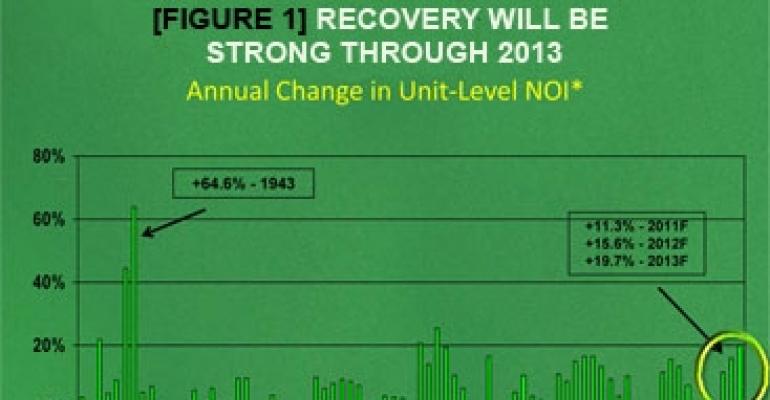

SAN DIEGO — At long last the struggling U.S. lodging industry can see light at the end of the tunnel. While net operating income (NOI) for the typical hotel is projected to fall 5.3% in 2010, that pales by comparison to the record 34.9% drop last year, according to Atlanta-based PKF Hospitality Research. The picture is expected to brighten considerably in 2011 when NOI is forecast to climb 11.3% and accelerate through 2013 [Figure 1].

While the pace of decline is moderating, at the moment it’s hardly a feel-good story for hotel owners who are facing weak consumer demand and falling room rates. The persistent decline in average daily rate (ADR) is expected to reach eight consecutive quarters before turning slightly positive in the fourth quarter of 2010. And even then the increase is projected to be a scant 0.8% on a year-over-year basis.

“Last year was certainly awful, and we believe that this year will be weak as well,” said Mark Woodworth, president of PKF Hospitality Research, during a speech delivered Monday afternoon to several hundred hospitality professionals attending the ninth annual Americas Lodging Investment Summit (ALIS). The Hilton San Diego Bayfront hotel is the site of the three-day event that ends today.

“Profit growth will return in 2011 as occupancy and ADR both accelerate, leading to double-digit gains,” explained Woodworth. “Sustained bottom-line growth will return for the foreseeable future thereafter, but perhaps not soon enough for some.”

Working through the pain

According to Trepp LLC, the performance of hotel loans originated, packaged and sold as commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) continues to deteriorate. Nearly one in five CMBS loans in the hotel sector was at least 30 days delinquent at the start of this year [Figure 2].

One question raised at ALIS: To what extent is a special servicer willing to work with a financially troubled borrower before it either forecloses on the property and takes back the collateral, or sells the mortgage note?

Just because a loan becomes delinquent doesn’t automatically mean the borrower will default, Woodworth pointed out. “Borrowers can recover, and lenders can rework their terms.” And there appears good reason to do so.

Woodworth cited a 2004 industry study conducted by Brian Lancaster and Davis Cable that focused on CMBS loans issued during the period 1992 through March 2003. The default rate among hotel loans was 7.2%. The average loan loss severity as a percentage of the loan balance at the time of default was a whopping 48.2% for the hotel sector. “Thus, there often is a significant motivation for the lender to avoid default, if possible,” emphasized Woodworth.

Where are cap rates headed?

A combination of a lack of liquidity and the absence of income growth has lifted capitalization rates to peak levels. (The cap rate is the initial return to the investor based on the purchase price and NOI. The higher the cap rate, the lower the purchase price.)

The average hotel cap rate bottomed out at 7.6% in 2007 during the height of the bull run in commercial real estate and has since climbed to a cyclical peak of approximately 10%, according to PKF. Its forecast calls for the average hotel cap rate to hold steady this year before falling to 9.7% in 2011, 9.2% in 2012 and 8.7% in 2013.

“An increase in profits and the reduced risk perceived in the marketplace will overcome escalating interest rates. Cap rate compression will occur as a result,” said Woodworth. PKF’s cap rate forecasting model takes into account interest rates, cash flows, system-wide liquidity and volatility.

“Although the cumulative loss in value has been substantial since 2008, significant asset appreciation will commence this year and persist through 2013 as cap rates fall further in response to stabilizing incomes,” added Woodworth.

The 34.9% year-over-year decline in profits realized by the average U.S. hotel in 2009 — combined with an increase of 210 basis points in the cap rate during the same period— has resulted in a stunning loss in asset value. “The cumulative decline that we are forecasting of a minus 51.5% exceeds the drop in value estimated for the 2001 to 2003 period,” said Woodworth.

Hazards of forecasting

The sharp drop in the financial performance of the U.S. hotel sector in 2009 forced researchers to revise their forecasts much more than usual as the year unfolded. But then again, it was a most unusual time.

“At ALIS 2009, the economic recession was just over a year old. The panic on Wall Street was in its fourth month, and our new president was just checking into the White House,” Woodworth reminded the audience. “Lodging fundamentals were contracting dramatically, and uncertainty was rife.”

At the start of 2009, PKF projected a 9.8% drop in revenue per available room (RevPAR) on a year-over-year basis. But by summer of 2009, PKF was calling for a 17.5% drop in RevPAR as job losses piled up and consumer spending tightened. That revised forecast turned out to be nearly spot-on as RevPAR actually fell 16.7% in 2009.

The occupancy forecast for the U.S. hotel sector underwent similar revisions during 2009. At the start of the year, PKF projected the average occupancy rate of U.S. hotels for all of 2009 would be 57.2%, but at mid-year that figure was revised downward to 55.5%. The actual number turned out to be 55.1%.

It’s little wonder. The economy has shed about 7.1 million jobs since the recession began in December 2007. The national unemployment rate, which currently stands at 10%, is expected to peak at 10.5% in the third quarter of 2010, according to Moody’s Economy.com.

Supply overhang

As if it didn’t have enough to contend with, the hotel sector has been hampered by an imbalance between supply and demand. In the fourth quarter of 2009, for example, demand fell by 2.7% compared with the same period a year earlier. Supply, however, rose by 3%. That gap is expected to narrow considerably over the course of 2010.

“In each of the previous two downturns, the volume of room openings began to diminish within two to three quarters after the recession began. In the current episode the opposite occurred,” noted Woodworth.

“Supply growth accelerated and remained elevated for almost two years after the Great Recession began in December 2007,” Woodworth also pointed out. “We are just now beginning to see year-over-year supply increases subside — an important and certainly welcome change.”