Savanna, a New York-based real estate private equity and asset management firm, last week acquired 31 Penn Plaza, a 18-story, 444,000-square-foot multi-tenant office building at 132 West 31st Street in a reported $130 million deal.

The firm plans to undertake a $26 million capital improvement plan to update the building and lease the available office space. Specifically, Savanna is looking to capitalize on a 160,000-square-foot block of contiguous space that it will market as a “building within a building” that features its own dedicated entrance and elevator, and offers prospective tenants a branding opportunity on the interior and exterior of the building. It has appointed Jones Lang LaSalle as leasing and property manager.

It bought the property from a joint venture between C&K Properties and Zamir Equities, which was advised by Jones Lang LaSalle in the off-market transaction.

It’s just the latest acquisition for the firm, which has been the most active buyer of Manhattan office properties over the past two years. It has acquired eight projects since the end of 2009 for a collective outlay exceeding $750 million, according to New York City-based research firm Real Capital Analytics.

For the most part, the firm has attempted to snatch up troubled assets (or properties from troubled borrowers) where it can come in and quickly improve the building.

In the case of 31 Penn Plaza, the firm completed a straight acquisition. But it’s also acquired properties by buying debt.

The case of 80 Broad Street

For example, in the case of 80 Broad Street in Lower Manhattan early this year, it prepared for a lengthy siege, Savanna knew that the office tower’s owner, a partnership of Swig Equities and Broadway Management, was in hot water. A $12 million mezzanine loan on the 417,000-sq.-ft. property had soured, and Cushman & Wakefield was shopping the defaulted first mortgage, which had more than $98 million in its principal still on the books.

Savanna negotiated simultaneously on several fronts to acquire the debt on the property, clear its liens and take over as owner. Savanna obtained the first mortgage on 80 Broad Street for $66.3 million, a 33% discount from the $98.4 million the borrower still owed. It picked up the $12.5 million mezzanine loan for $1.6 million. All told, the property carried $266 of debt per sq. ft.

At that level, the private equity firm expects to generate juicy annual returns of 20% or more for its investors simply by performing needed maintenance and leasing the property at market rates. Current repairs include replacing the elevator and finishing out model offices that will be ready to show prospective tenants when the space re-launches in the first quarter next year.

Moreover, rather than lock the borrower out of the deal, Savanna retained the former owner to stay on and manage the building. “He knows the property better than anyone, and that gave him an additional incentive to work with us on the transfer of the deed,” says Nicholas Bienstock, a managing partner at Savanna, referring to Swig president Kent Swig. “To avoid a lengthy legal battle, we needed to make a deal that not only made sense for Savanna, but also for the borrower.”

Major force

Private equity investors constitute a major force in commercial real estate today. Some 435 private equity funds are focused on commercial properties, targeting aggregate commitments of $138 billion, according to London-based research firm Preqin.

And fund raising is accelerating: 18 commercial real estate funds reached a close in the second quarter this year, collectively raising $11.2 billion. That’s up from $8.9 billion raised in the first quarter of 2011 and $7.1 billion in the fourth quarter of 2010, according to Preqin. Of the total from the second quarter, 10 funds and $8.6 billion were earmarked for North America.

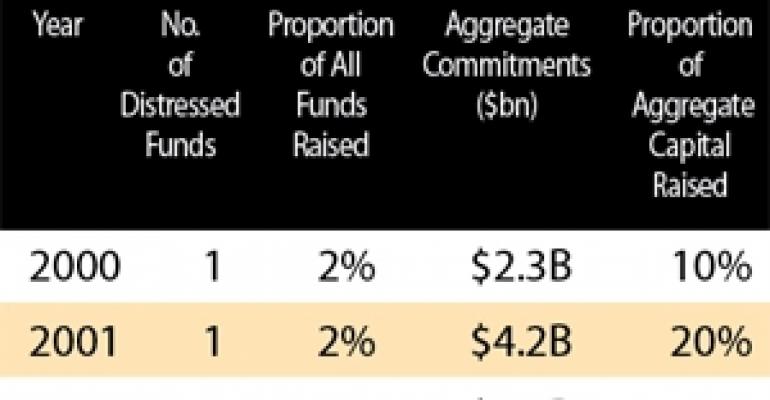

Increasingly, those funds are earmarked for distressed opportunities. Overall, 22% of the capital raised in 2010 is allocated for some degree of investment in distressed assets, and the $21.6 billion collectively raised by those funds represents nearly half, or 48%, of aggregate capital raised in the sector.

That’s a marked change from a few years earlier—before the Great Recession and credit crisis. From 2000 through 2006, less than 3% of real estate private equity firm targeted distressed properties as potential acquisitions.

“Since the downturn of 2008, we’ve seen a surge of funds targeting these [distress] opportunities,” says Andrew Moylan, Preqin’s manager of real estate data. “It’s always been a part of the industry, but it was a niche area.”

In part, private equity firms moved into distressed acquisitions because they are seeking returns higher than those available on other commercial real estate investing opportunities.

“Where private equity has had more success is by moving down the quality scale,” says Jim Sullivan, managing director of REIT research with Green Street Advisors, a Newport Beach, Calif.-based consulting and advisory firm. “Where private equity has had more success is by moving down the quality scale. They are buying a tent that’s a little less crowded.”