The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) policy recommendations for banks dealing with troubled commercial real estate loans appear to be easing the burden on borrowers facing falling property values.

In October, the FDIC, along with the Board of Governors of Federal Reserve, the National Credit Union Administration and the Office of Thrift Supervision, issued a policy statement advising banks to extend and/or restructure loans backed by income-producing properties whenever possible in order to minimize losses. This approach should help banks avoid selling high quality assets in a distressed market. Instead banks will have time to wait for property values to recover. So far, that is exactly what is playing out. Industry observers say banks have been eager to take advantage of the new rules.

This policy, along with the recent easing of regulations governing modifications and extensions of loans packaged into commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), should reduce defaults in the near-term. But whether the forbearance approach will prove effective in the long run will depend on the timing of recovery in the investment sales market, says Jon Southard, principal and director of forecasting with CBRE Econometric Advisors, a Boston-based research firm.

“In an ideal situation, it will lessen the problem—if the capital markets get better,” he notes. “But it certainly poses the risk of postponing the problem if neither the capital markets nor the economy improve.”

According to the FDIC guidelines, banks should conduct workouts with borrowers that are able to make their debt service payments. The modifications can take the form of extensions, issuance of additional credit or restructuring loans entirely. In many cases, the banks are choosing to extend loan terms by two or three years, in exchange for an interest rate increase and a partial pay down, according to Jim Spitzer, partner in the New York City office of Holland & Knight, a global law firm. Spitzer notes that since the FDIC recommendations went into effect, loan workout conversations with bank representatives have gotten easier. Spitzer contrasts the situation today with the 1990s when bank executives had the attitude that they manage commercial real estate assets better in-house and were content to repossess assets. Today, “the banks don’t want these properties back.”

Investment sales brokers are seeing the effectiveness of the rules in cases where owners that were ready to sell in order to pay down debt instead have been saved by extensions and restructurings.

“I’ve even seen situations where developers are in bankruptcy and the bankers have not foreclosed on the real estate,” says Bernard J. Haddigan, senior vice president and managing director of the national retail group with Marcus & Millichap Real Estate Investment Services, an Encino, Calif.-based brokerage firm. “Most of them seem to be extending the loan and choosing not [to exercise] the right of foreclosure.”

In fact, the recent extension agreement reached by bankrupt retail REIT General Growth Properties on 70 of its secured mortgages might serve as a framework for lenders and borrowers trying to work out distressed situations, according to analysts. The agreement, subject to approval by the bankruptcy court and General Growth’s class B note holders, extends the loan terms by an average of 6.4 years. In exchange, General Growth has agreed to concessions on amortization and reserve terms on the loans.

The FDIC recommendations might prove helpful because today a large number of defaults in the commercial real estate sector are due to an overall decline in property values, rather than to missed debt payments or bankruptcy situations, says Suzanne Mulvee, senior real estate economist with Property & Portfolio Research (PPR), a Boston-based real estate research firm. That means that in many cases, a two- or three-year extension might save borrowers from defaults and lenders from having to recognize large losses.

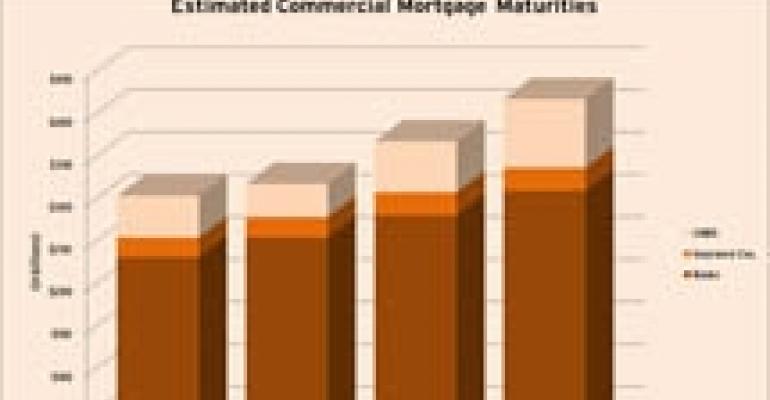

In addition, the new recommendations might help banks deal with good credit owners who are facing difficulty securing refinancing for maturing loans. The banks face approximately $257 billion in maturing commercial real estate loans in 2010, followed by $283 billion in 2011 and $312 billion in 2012, according to research from ING Clarion Partners.

There are approximately “$163 billion worth of loans [eligible for these workouts] that will mature between 2009 and 2010, and with an optimum extension of four years, it will reduce the loss by approximately $3 billion, simply because there will be some recovery in property values after four years,” says Pooja Sharma, senior debt analyst with PPR.

“The alternative is to push the borrower into the marketplace and what you are going to suffer is greater if you do not extend,” adds Mulvee.

However, some industry insiders worry that FDIC’s approach to the debt crisis might prolong the downturn. The idea of extending loans on performing properties makes sense in theory, but in practice, the best quality real estate assets are normally financed by CMBS loans, not banks, says Haddigan. Most bank-originated loans come from acquisition, development and construction, as well as buildings owned by local businesses.

“It’s unlikely that you will have a functioning food-anchored shopping center that’s financed by bank debt,” notes Haddigan. That means many extensions might be applied to assets that are not likely to recover in value for more than a decade. What’s more, since under the new guidelines the banks will have less money coming in from loan maturities, they will have less money for new lending, adds Spitzer.

“Bank debt is different than CMBS debt, and I don’t see how just putting band aids on some of this stuff is going to fix anything,” Haddigan says. “My concern is this is going to prolong the recovery because [this prevents] risk assessment. I think that creating a modern Resolution Trust Corp. kind of structure would make a lot [more] sense.”

–Elaine Misonzhnik