After taking a beating in 2009, private equity firms are once again in the market prowling for retail buyout opportunities.

Most prominently, speculation has mounted that Green Equity Investors may buy discount chain BJ’s Wholesale Club. The private equity firm has already amassed a 9.5 percent stake in the company by buying 5.1 million shares. Observers are wondering if that’s a prelude to a larger bid.

Besides BJ’s, noted investor Ron Burkle, founder of Yucaipa Companies LLC, has spent much of the first half of the year stalking Barnes & Noble while also investing in American Apparel and courting Barneys New York.

But while private equity players might once again be looking to the retail sector to generate returns, don’t expect the volume of deals to come anywhere close to the levels seen at the peak of the market, in 2006, industry sources say.

For one thing, private equity firms have cash on hand, but securing acquisition financing remains difficult. A major driver of the last buyout wave was that buyout debt could be securitized in collateralized loan obligations. In 2009, CLO issuance in the U.S. totaled $26.5 billion, the lowest volume in more than 10 years, according to Moody’s Investors Service. It’s only been in recent months that the CLO market has started to pick up. Since leverage is central to generating the returns private equity firms are pursuing, a robust credit environment is central to a lively takeover market.

In addition, another driver of retail deals in the past had been the value of the real estate holdings some companies controlled. In the past, private equity players would often sell most or all of the retailers’ owned stores. At the peak of the market, in fact, it was reckoned that some firm’s real estate holdings were worth more than the firm’s total market capitalizations. But given today’s high vacancy rates and commercial real estate values down 40 percent from market peaks, it is difficult to find takers for those spaces, unless they came at a significant discount.

Another strike against retail operators is that the worst consumer spending climate in decades means that private equity investors won’t be as eager to take on just any retailer as long as it comes with a brand name and a large fleet of stores.

Instead, many of the takeovers that will occur this year will be driven by retail companies looking to make opportunistic plays for expansion with or without the aid of private equity, says Bob Filek, partner in the transaction services group of PricewaterhouseCoopers, a global professional services firm. And a large percentage of those deals might involve U.S. retailers buying companies in other parts of the world, including Asia, Europe and Latin America.

“The domestic retail mergers and acquisition activity will be very limited and probably focused on those companies in need of stronger financial footing to weather the downturn in consumer demand,” Filek says.

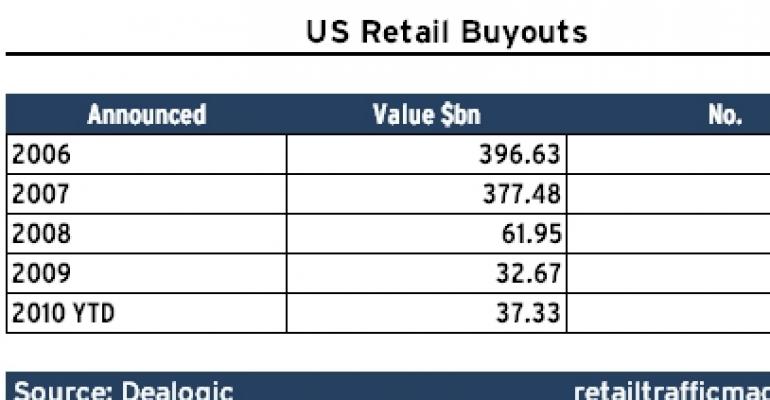

Year-to-date in 2010, the volume of retail buyouts in the U.S. has totaled $37.3 billion spent in 251 deals, according to Dealogic, a global research and consulting firm. That already represents an increase over 2009, when the total volume of retail buyouts for the entire year came to $32.7 billion, spent in 506 deals. It also goes against the trend in the U.S. mergers and acquisitions market overall, where the dollar volume of announced transactions in the first five months of the year, at $317 billion, was below the volume recorded during the same period last year, according to data compiled by Thomson Reuters.

But the volume of retail deals in 2010 still falls far short of the peak years in retail mergers and acquisitions. For example, in 2006, there were 1,095 retail buyouts in the U.S., totaling $396.6 billion.

The year-over-year increase in deals in 2010 has likely been driven by a combination of an improved outlook on the economy and the availability of debt capital for the right transactions, according to Craig Johnson, president of Customer Growth Partners, a New Canaan, Conn.-based consulting firm.

Earlier this year, the CLO market began showing signs of life, with several large banks underwriting multi-million dollar issues. Nevertheless, the terms of the loans remain arduous, making large buyout deals in the retail sector highly unlikely, says Howard Davidowitz, chairman of Davidowitz & Associates Inc., a New York City-based retail consulting and investment banking firm.

“The banks got destroyed because they had given private equity very easy covenants, so the conditions of the loans are now much tighter,” Davidowitz says. “It’s more difficult to raise debt and debt is more expensive, and most importantly, the conditions of the debt are much more difficult.”

As a result, whatever private equity takeovers had taken place in the retail sector this year were likely driven by the combination of very low valuations and unique turnaround opportunities, says Davidowitz. For example, for much of May and June, BJ’s shares had been trading at values in the low- to mid- 30s. The 52-week high for the company is $44.27 per share.

Meanwhile, at the opening of the trading day on Tuesday, shares of American Apparel went for $1.65 apiece. The company’s 52-week high is $4.20 per share.

“You buy the shares for nothing and hope for the best,” says Davidowitz of investors’ acquisition strategy. “So you buy a retailer that’s selling at a giant discount and then what you do is work against the betting average. If one or two [of the deals] works out, you make a fortune.”

Price is no longer the only driving force behind private investors’ decision to buy retail, however, Davidowitz notes. After the sector turned out to be a huge money loser in 2008 and 2009, with many of the bought out chains moving into bankruptcy and ultimately liquidating, private equity players are paying more attention to the retailers’ turnaround potential.

Blockbuster, for example, might offer a unique turnaround opportunity because one of its main competitors, Movie Gallery, went out of business earlier this year. That might make it easier for Blockbuster to survive if it changes its operating model to fit in with the evolving market—for example, by transforming itself into a DVD rental kiosk chain.

There’s another reason why deals will increase. The money private equity firms raise has to be spent in a certain time frame or returned to investors. Therefore private equity players will look to deploy the capital they have raised. That will make them more likely to act if attractive buyout opportunities present themselves. But given the state of the retail market right now, they might be much more cautious than they have been historically, Davidowitz says.

“If you are investing in retail right now, you are a betting on the consumer and that’s a very hard bet,” he notes. “For private equity to succeed, they have to have a vision of how it’s going to work. I think private equity has a whole different idea right now and that’s why they are doing small deals.”

The medial deal size for all mergers and acquisitions today is $107 million, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.