Commercial real estate lenders have prolonged dealing with distressed loans for close to two years. But they may no longer be able to remain passive.

Speakers at the Bankers Forum on Distressed Properties and Real Estate Loan Workouts, which took place in New York City on Apr. 19 and 20, said they are seeing the amount of distressed retail property continue to grow. In spite of a recent spike in retail sales, the leasing market remains challenging and retail property NOIs continue to fall. Up to now, banks have spent much of their time dealing with troubled construction and residential loans. But in 2010, they are turning more attention to resolving office and retail loans.

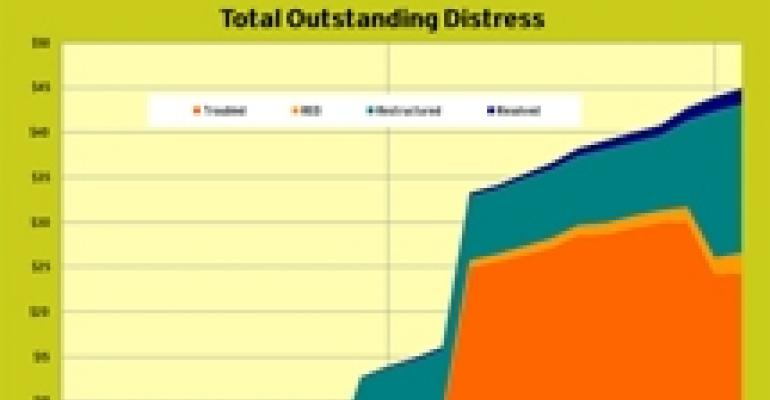

As of February, there were $2.3 billion in retail properties counted as real estate owned (REO) on bank balance sheets, up from a level of $450 million 12 months ago, according to Real Capital Analytics (RCA), a New York City-based research firm. A further $24.3 billion in properties were identified as distressed, up from $7 billion 12 months ago.

“Currently, the retail sector [probably] causes the most concern, just because of the economy,” said Derrick D. Cephas, president and CEO of Amalgamated Bank, a New York City-based institution that holds approximately $1 billion in diversified commercial real estate debt. “It’s not because of poor structure or poor concept.”

Cephas, along with Pat Goldstein, vice chairman of Emigrant Realty Finance Inc., the commercial real estate arm of Emigrant Bank, said that lenders try to work out troubled loans with borrowers when they are looking at properties that continue to generate cash flow, but the process is not always easy. The terms of traditional loans in the $10 million to $20 million range can often be changed if borrowers have additional real estate that can be pledged as collateral, Cephas said. To make this an attractive proposition, lenders try to offer terms that are favorable enough for borrowers to recoup most, if not all, of their investments in the assets.

Approximately $16.5 billion of loans on retail properties have been restructured in the past 12 months, according to RCA data. A big chunk of that total is due to General Growth Properties’ ongoing restructuring.

But one of the biggest challenges in today’s market, according to Goldstein, comes from large syndicated loans that require a consortium of lenders to agree before an extension is granted. Some banks don’t like the “pretend and extend” approach. Others face directions from the FDIC that require them to write down cash-flowing properties that face technical defaults. Still others—hedge funds, for example—might stand to profit when assets enter foreclosure because of short positions, so there is pressure to not seek any remedies. As a result, Goldstein estimates that Emigrant officials spend about half their time talking with other lenders rather than working with borrowers.

Meanwhile, banks are beginning to take back properties where rental incomes have deteriorated enough to affect cash flows. Once those properties enter REO, banks might try to retain the assets and invest additional funds in class-A and class-B centers in primary markets. However, banks are trying to move less attractive assets as soon as possible, said Michael Morris, managing director of real estate capital markets with Zions Bank, a Salt Lake City-based lending institution. “We don’t want to hold assets for longer than 90 days in the REO bucket. That’s our philosophy,” Morris notes.

Note sales continue to be the preferred strategy for disposing of troubled loans in the current environment as buyers’ interest in buying notes is more robust than interest in purchasing underlying properties. The problem is few buyers want notes on largely empty retail centers, according to Lorne Polger, senior managing director with Pathfinder Partners LLC, a San Diego, Calif.-based opportunistic investor that purchases both senior debt and underlying real estate assets. Pathfinder, like many other opportunistic investors in the market today, looks to achieve double-digit returns on the deals it makes. That requires investment in stabilized assets.

There are, however, strategies the banks can adapt to make their notes more attractive to potential buyers, says Polger. He recommends offering at least some kind of leverage for deals and marketing the assets through as many channels as possible. He also cautions banks not to wait too long to move distressed debt off their balance sheets.

“We’ve seen innumerable times when banks call us nine or 10 days before the end of the quarter to ask us to take something off their books,” he says. “That’s good for us, but you are not going to get the highest price” by asking investors to close the deal in a week’s time.

—Elaine Misonzhnik