Though manufacturing GDP has seen overall growth of 13 percent in the past 10 years, and the industry has gained from the additional return of offshore facilities, continued job elimination will remain an important factor in industrial real estate decisions.

During a JLL webinar about the future of U.S. manufacturing, held on Nov. 11, experts said that it is clear that more companies today are investing in or considering new manufacturing facilities stateside. The only problem, said JLL executives, is that the skill level required for these new facilities has risen above what the average community can provide.

“The skill requirements for jobs in the United States are more advanced than ever before, and the reality is that there’s a tremendous shortage here for that type of labor,” said Shannon Curley, vice president of JLL’s business consulting group. “We have a legacy manufacturing base of labor, and a shortage of new technical talent. We have to figure out how to educate the workforce for these needs.”

Matt Jackson, managing director with the group, noted that in 1978 only 20 percent of manufacturers required workers to have more than a high school education. By 1992, however, that figure rose to 50 percent, and by 2020, about 65 percent of workers will need high-level training, Jackson says.

“One really telling statistic is that as of August 2014, about 9.6 million were unemployed, but about 4.8 million jobs were left unfilled,” Jackson said. “Manufacturers don’t have a problem getting the lowest-skill laborers, but they are having tremendous difficulty sourcing skilled labor, across all industries.”

The markets boasting the most skilled labor are attracting the greatest level of attention from companies looking to relocate or open new manufacturing hubs, JLL executives said. Computer and electronics companies, as well as those in the aerospace industry, are focusing mostly on the coasts, as well as pockets in Texas where high tech workers have been congregating. The automotive industry is still dominated by Detroit and Ohio, but jobs and facilities have started to shift south into Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama and the Carolinas.

Curley said GDP is still up overall, at 13 percent growth, for all industries since 2004. Electronics manufacturers have seen the strongest growth, at 103 percent, followed by agriculture, construction and mining sectors. Textile mills have struggled the most, with much lower than average growth, along with petroleum, coal and furniture products manufacturers.

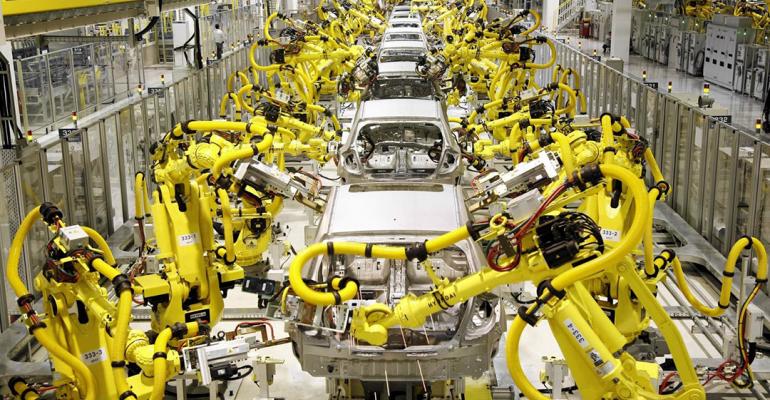

Manufacturing jobs, however, don’t follow the same growth lines. Electronics and automotive employment is down about 20 percent as those industries use robotics and find efficiencies to eliminate workers. Even if companies look to add facilities, there will still likely be a continued slide from 12 million manufacturing jobs today to 10 million in 2028, according to JLL’s estimates.

“Those industries suffering from poor GDP and job growth expectations will likely be looking for dispositions and consolidations, [rather] than acquisitions and greenfield purchases,” Curley said. “Other sectors that are ripe for growth will likely be looking for areas that have those high-skilled workers in place.”