In many cities and towns across the country, if developers want to build new apartments, they will have to make at least a few of those apartments affordable to low- and moderate-income families.

“More and more cities and counties are looking at inclusionary housing in one form or another to deal with the incredibly high rent,” says Maya Brennan, vice president for the Urban Land Institute’s Terwilliger Center for Housing.

Inclusionary housing policies require developers to include affordable housing when they build in the desirable places targeted by the programs. These policies are becoming much more effective as more developers concentrate their energies on prime submarkets, such as bustling central business districts or towns and neighborhoods served by mass transit. As these places become more desirable, more developers are willing to include affordable as part the high cost of development there.

Hundreds of jurisdictions throughout the U.S. now have inclusionary zoning laws in place—most adopted within the past 10 years, according to a September 2015 report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The programs include 512 inclusionary housing programs in 487 local jurisdictions in 27 states and the District of Columbia. Nearly two-thirds of these are concentrated in New Jersey and California. States including Massachusetts, New York, Colorado, Rhode Island and North Carolina each have 10 or more local programs.

Place-making favors inclusionary housing

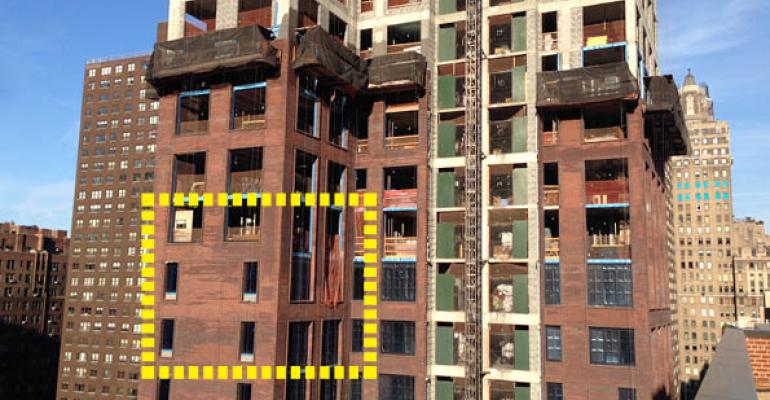

Inclusionary housing programs are thriving as more developers focus on “core” real estate markets in bustling neighborhoods, with many transit options and amenities like shopping and restaurants a short walk away. Currently, about a quarter of all the new apartments now under development are squeezing into central business districts, according to data from CoStar.

That’s great news for officials considering inclusionary housing policies for desirable submarkets. Inclusionary housing policies only work when the policies target irreplaceable, desirable locations—so that developers are willing to include affordable housing in exchange for the right to build there. Inclusionary housing is much less effective if a developer can simply find an attractive site in a neighboring town or unincorporated area that captures the same market of potential residents. Not long ago, developers could build garden apartments on almost any green field near a highway entrance on the edge of a growing metro area. That’s decisively changed as developers and investors pile into core real estate markets or design new town center developments.

That’s great news for officials considering inclusionary housing policies for desirable submarkets. Inclusionary housing policies only work when the policies target irreplaceable, desirable locations—so that developers are willing to include affordable housing in exchange for the right to build there. Inclusionary housing is much less effective if a developer can simply find an attractive site in a neighboring town or unincorporated area that captures the same market of potential residents. Not long ago, developers could build garden apartments on almost any green field near a highway entrance on the edge of a growing metro area. That’s decisively changed as developers and investors pile into core real estate markets or design new town center developments.

Inclusionary housing programs get tough

Not only are more jurisdictions adopting inclusionary housing rules, but those rules are getting tougher. Areas that once asked developers to include affordable housing in exchange for a variety of incentives are now more likely to demand that affordable housing is included in new development.

“There has been a push, where inclusionary housing has been voluntary, to make it mandatory,” says Brennan.

Mandatory programs are more common than voluntary programs: 83 percent of the 512 programs identified by the 2014 Network-CHP Project were mandatory, according to data from a report by Lincoln. However, even mandatory programs often offer developers incentives to help make their developments profitable, even including the affordable housing they will have to include. That’s because inclusionary housing programs fail if developers decide not to build. The most common incentive is the ability to build with increased density, but other common incentives include parking or design waivers, zoning variances, tax abatements, fee waivers and expedited permitting.

New York’s inclusionary housing program is currently voluntary. Developers who want zoning changes to build larger projects are asked to include affordable housing in their projects. Mayor Bill de Blasio has suggested the city can ask for more from developers. However, exactly how much more an inclusionary program can demand from developers changes from neighborhood to neighborhood.

“In many of the city’s neighborhoods, rents are likely insufficient to justify new mid- and high-rise construction, let alone cross-subsidize the creation of new affordable housing through up-zoning,” according to an analysis from New York University’s Furman Center. For example, for a high-rise building in a very high-rent neighborhood, the city could require that about 28 percent of any additional zoning density be affordable if the building is subject to full property taxes. This share increases to 61 percent with full property tax exemption, according to the Furman Center.