For the past couple of years, investors in nonperforming loans have besieged bankers with inquiries. Frequent responses from bankers have ranged from “we have no problems” to “we’re handling them internally,” or “we’re waiting for the real estate markets to turn around.”

Two and a half years since the official beginning of the recession, many bankers have changed their tune. Now they’re asking, “Where do you think these loans will trade?”

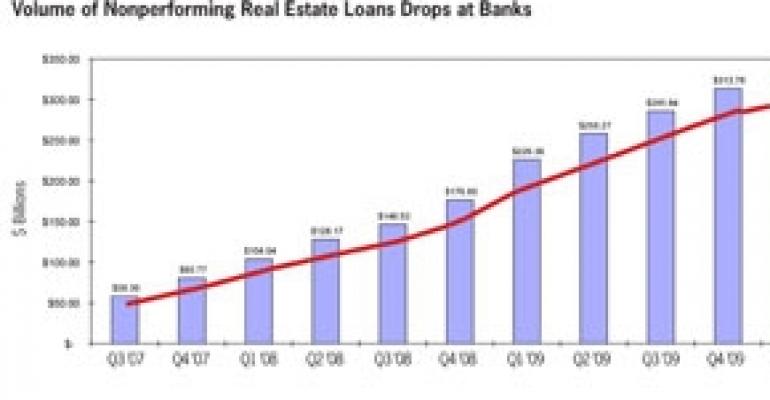

Evidence of this change in attitude is growing. For the first time in this cycle, nonperforming real estate loans dropped in the second quarter of 2010, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Nonperforming loans are defined as loans 90 or more days past due plus nonaccruals, or loans that are no longer earning interest.

This $15 billion quarter-over-quarter reduction in nonperforming loans is due in part to troubled debt restructuring and some foreclosures. But as one prominent large bank analyst recently noted, the banks he covers disposed of $5 billion in nonaccrual loans during the second quarter, a steep uptick from the first quarter. What’s changed and who are the winners and losers when these loans start to transfer from bankers to investors?

Banks’ improving positions

First, it’s important to remember that not all banks are in the same position, face the same pressures or can tolerate the shock of selling nonperforming loans at a loss to investors. While FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair hailed “the best quarterly profit for the banking sector in almost three years,” progress among banks is uneven.

For the second quarter of 2010, although large banks set aside less for their loan loss reserves than in recent quarters, smaller banks continued adding to their reserves at elevated levels.

For many banks, low interest rates in the first half of 2010 have enabled them to rebuild capital. While interest income (the yield on banks’ earning assets) decreased 2.4% from the first half of 2009, interest expense (what banks pay their depositors and lenders) dropped a whopping 30%. Meanwhile, banks’ capital gains from selling securities more than tripled over the same period.

For those lucky banks able to attract deposits at near zero percent interest and who were able to sell their investments at large gains, the pain of selling nonperforming loans is offset by strong capital and net interest margins (the difference between the cost of funds and the yield on assets).

Second, after increasing loan loss provisions by more than $500 billion over the last two and a half years, two important lines have begun to cross. The widely reported bid-ask spread represents the difference between the prices at which banks can tolerate selling nonperforming loans and the prices investors want to bid for them.

The bid side is based on investor appetite and yield requirements, while the ask side combines the amount of loss against the unpaid principal balance of the loan that banks are willing to tolerate and how much of the loss the bank has already reserved.

For banks that aggressively set aside reserves against nonperforming loans, bids from reasonable investors are approaching tolerable price levels. At the low point for banking problems, investors routinely sought 25% yields. With relatively few high-yielding investment alternatives, many of these investors are now willing to accept yields below 15%.

Over time, the offering prices from banks have declined and quotes from buyers have ratcheted higher. The lines for prices at which loans are offered and investors are bidding have begun to intersect.

Third, for banks in relatively healthy lending markets, the appeal of simply growing their portfolios of U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities is losing its shine. From June 2008 to June 2010, banks’ securities portfolios grew by more than half a trillion dollars while loan portfolios shrank by more than $700 billion. In times of greater sensitivity to credit risk, this makes sense.

Bank motivations

But reduced risk comes at a cost of reduced yield. Regulators also are beginning to turn their attention to increasing interest rate risk as banks plow short-term deposits into long-term, fixed-rate securities. This could prove problematic for banks when interest rates inevitably turn up.

Banks with clean balance sheets and relatively attractive lending opportunities can more readily address creditworthy loan requests. They will begin shifting investable cash flow into new loans. For banks with broader ambitions, high-performing loan portfolios position them well for the coming consolidation.

As Kingsley Greenland, CEO of DebtX, one of the country’s top loan seller advisors, told me: “There is a race on by banks to clean up their balance sheets so that they can be the first to be healthy in their market and participate on the buy side of the coming M&A (mergers and acquisitions) wave.”

Regrettably, many conscientious bankers who began scrutinizing their portfolios of nonperforming loans three years ago now have a downbeat assessment of their near-term real estate prospects. Many real estate projects will not recover in the foreseeable future.

This turn in attitude will never make headlines or appear in print. But many clear-eyed bankers are objectively reviewing their nonperforming loans and asking a compelling question: “What am I waiting for?”

Risks and opportunities

Plenty of anecdotal evidence is in the market that banks are beginning to liquidate their nonperforming loans and the vast majority of these dispositions are real estate-related. If this is generally true, what does it mean for real estate borrowers, developers and investors?

If you’re one of millions of defaulted borrowers, prepare for a sudden change. The waiting game many of you have played with your banker may end abruptly if your loan transfers to an investor with no historical stake and a low accounting basis.

If you’re an investor with money to invest or access to funding, sound out your local banker or their advisor with troubled properties in your selected submarket and preferred property type. For the right selling bank and the right loan, there are deals to be cut.

Brian Olasov is a managing director in the Atlanta and Washington, D.C. offices of McKenna Long & Aldridge LLP, where he focuses on real estate capital markets, troubled mortgage loans and banking challenges. He can be reached at [email protected].