His latest restaurant, The Boathouse at Disney, was still months from its opening Monday, and yet Steve Schussler was bothered by waves.

Schussler was given a pair of mockups of the uniform created for the new restaurant designed to make the waiters and waitresses resemble the crew of a cruise ship. The logo had “The Boathouse” on a red banner atop a gold and yellow anchor. In one of the options, that anchor was underscored by light blue waves that were almost unnoticeable against the Navy blue shirt. In another, the waves were gold.

Schussler didn’t like the blue waves. And just to prove his point, he called in his staff and asked them to pick which uniform is better. All but one of them chose the uniform with the gold waves.

It may seem surprising that the creator of some of the world’s most expensive restaurants, some of which cost tens of millions of dollars to build, gets bent out of shape over something as subtle as waves on a uniform shirt. But to Schussler, that is a vital part of his job.

“How can you call yourself a creative and not have that kind of attention to detail?” Schussler asked.

He and his company, Schussler Creative Inc., are the brains behind some of the flashiest restaurants in the country. Schussler created Rainforest Cafe, which opened at the Mall of America in 1994 and put diners in the middle of a fake rainforest, complete with vast amounts of plastic greenery, mist and an animatronic alligator.

Or there’s T-Rex, which makes Rainforest look like a quiet sidewalk café. It has massive animatronic dinosaurs, a giant octopus and regular performances of the meteor shower that destroyed the dinosaurs.

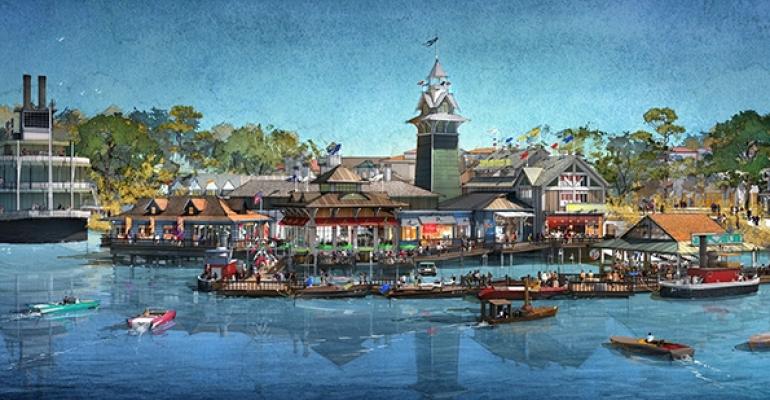

The Boathouse, which opened on Monday, isn’t quite that ostentatious. But it’s no less creative. The restaurant is a mammoth 23,000 square feet on a lake, with a 1940s-era boathouse motif and seats for 450 people. Amphibious crafts will go from the lake to a driveway next to the restaurant to give tourists a boat ride before their meal. Italian water taxis are also available to shuttle diners. There’s a flag-raising ceremony every day, with a bugler playing Reveille. While Schussler wouldn’t divulge how much the restaurant cost to build, he acknowledged that it wasn’t exactly cheap.

“With a project the scale and size of a project at Disney, you would imagine that it entails an awful lot of investment,” he said. “It’s substantially more expensive to build per square foot than a regular restaurant.”

But these facilities have something in common with the neighborhood pizza place down the block, Schussler said: Food trumps all. While he stresses over uniforms and gets excited over fake candles, he acknowledges that the most important aspect of the restaurant is still what’s made in the kitchen.

“The food has to be excellent,” Schussler said. “They come once for the wow factor. They come back for the food and the service. It’s more important to have good food and service and add the wow factor. All of these ingredients have to be put into a blender and mixed up.”

Schussler is a hyperactive 59-year-old. He keeps two cell phones, and his office has three computers hidden on his vast desk among the toys and statues and noisemaking buttons and framed pictures and copies of newspaper and magazine articles. A single question might generate an answer spanning eight subjects and take more than half an hour, and he might bring in some of his employees to provide supplementary information or help prove his point.

Schussler made a name for himself creating the eight-unit nightclub chain Jukebox Saturday Night in the 1980s before he came up with the idea for Rainforest.

To conceive it, he literally lived it, transforming his home into a rainforest. It required so much power that, he swears, DEA agents raided the home one night, thinking he was making meth. Instead, agents found a makeshift rainforest with lush greenery that at one time had been a home to parrots and a giant tortoise. He even kept a baboon there for a time.

Rainforest opened in the Mall of America in 1994. A few months later, the company had an IPO with just that one location. The stock prospered for a time in the mid-1990s, and the company opened 45 locations, but it ultimately ran into problems and was sold to Landry’s in 2000 for $125 million.

Inside Schussler's Lab

Schussler then started Schussler Creative and moved into a nondescript space in a ’90s-era business park. But the “nondescript” part ends the moment a visitor walks into the front door and is greeted by a six-foot tall statue of Mickey Mouse.

Every inch of space on walls and shelves in the lobby is occupied with pictures or posters or statues or model boats.

“Most people ask for an aspirin when they walk in the door,” Schussler joked.

Behind the lobby is the Schussler Creative laboratory, where the company creates mockups for potential restaurant concepts. Inside one is a wizard-themed concept complete with renaissance-style table setup, a wizard in the corner and a magic display. There are fake candles, too, the product of technology developed by Disney and later sold to a Minnesota company. Schussler gushes about them.

“I can’t believe how excited I get about candles,” he said.

The mockup of T-Rex is still here, in one room, where a visitor is greeted by a large, roaring tyrannosaurus rex, fake flames and a glowing “ice cave” that changes from one bright color to another, all in a makeshift, sequoia pine forest with vines and other dinosaur statues.

In another room is a mockup of a concept to be called Zi, which is intended as an upscale Asian-themed restaurant and has been in the works for 15 years. At that time, Schussler procured two rat-infested 40-foot containers loaded with broken pieces of 200-year-old Chinese history from the Qing Dynasty for a cheap price.

The pieces were part of large statues of warriors and ships made from whale and water buffalo bone. Schussler then asked Kim Anderson, his exhibits and logistics manager, to put it all together. The project took 15 years.

“This was all destroyed,” Anderson said. “I had no idea how to put it together.”

He also said that many of the pieces were mixed with rat carcasses and were covered in rat dung and urine.

“It smelled so bad,” he added.

Schussler comes up with the idea for a concept, and then he and his staff develop it inside the lab.

“We put a heart in it and a soul in it,” Schussler said. “We experiment with it every day, with everything from lighting to sound.”

Profit Drivers

Every concept appeals to all five senses.

His company then finds the locations where the concept will fit, and works to find someone to operate the restaurants. Schussler doesn’t operate the restaurants he designs.

Landry’s Inc., for instance, bought Rainforest Cafe in 2000, and now it operates Schussler restaurants like T-Rex as well. Gibson’s Restaurant Group, the Chicago-based owner of Gibson’s Bar and Steakhouse — and operator of five of the 100 highest-grossing independent restaurants in the country, according to Gibson’s — will operate The Boathouse.

The restaurant lab helps convince partners to take on the investment, because it tests the concept and its workability. Schussler will work on something for years before presenting it.

“He’s a really creative guy,” said Steve Lombardo, co-founder of Gibson’s. “He doesn’t just come up with an idea. He’ll actually build an idea in one of his warehouses. He plays with it. He does a lot before he says, ‘OK.’ There’s a lot of trial and error. And it’s not just the creativity. It’s the research that’s done.”

Because Schussler doesn’t design cheap restaurants, they have to be profitable for the business to work. But when they do work, a single restaurant can earn millions.

“You have to have a great operator, so bottom line it’s not 10 percent profit, it’s 20 percent profit,” Schussler said. “If it’s 10 percent profit, it’ll take until you and I are dead and buried to make up the cost.”

“You can make a lot more money if you can convince somebody to put $25 million into your operation,” he added.

Schussler gives that profitability a boost, however, by including a heavy retail presence in every restaurant he creates. At least 15 percent of every restaurant’s sales come through retail, he says.

T-Rex, for instance, does considerable business selling Build-A-Dino, a make-your own stuffed dinosaur done in partnership with Build-A-Bear. At Hot Dog Hall of Fame on Universal City Walk in Orlando, diners can buy a “Paint Your Own Wiener” kit, with paint and a toy dachshund, or wiener dog.

The Boathouse sells custom paddles and upscale, water-themed merchandise such as antique boating artifacts and Frederique Constant watches, which range in cost from $400 to $2,000. But it’ll also sell custom ducks, including a couple that are named Mrs. Quackcraft and Mr. Quackcraft.

“We want to give them a memory,” said Rae Olson, Schussler Creative’s vice president of retail. “This gives them something to take home.”

The retail area and other aspects of the restaurant, such as those amphibious cars or amphicars, along with souvenir photography, help make these giant restaurants more profitable.

“It’s a restaurant with many income streams,” Lombardo said. “It’ll be more profitable than a typical restaurant.”

Not everything Schussler tries works. But, he noted, “there’s a lot of things that do.” And when they work, the concepts are popular. Three of the most popular restaurants at Disney — T-Rex, Rainforest and a third, Yak & Yeti — are Schussler creations.

“For me, creating is a drug,” he said. “That’s the high I get: To create something that people think is out of this world; to create something that guests and families will talk about for years. I just like to take things to a different level.”