(Bloomberg Opinion)—Along Santa Barbara’s cherished Pacific beachfront, old campers, modified pick-up trucks and shabby cars are parallel parked on the adjacent road. It’s growing dark, and the denizens of these cramped, four-wheeled apartments are settling in for the night.

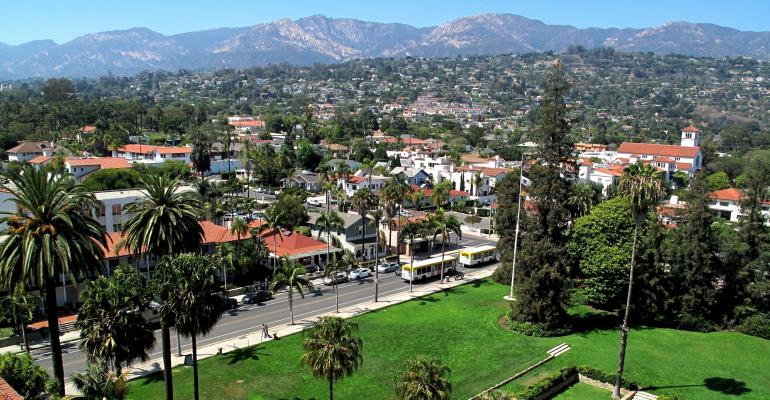

California remains a land of great beauty and soaring promise, with dynamic industries and spectacular vistas. But if the state does not aggressively address its housing crisis, its future is at risk.

The state is home to many of the nation’s least affordable metropolitan areas. A 2016 McKinsey report estimated that Californians pay $50 billion more for housing annually than they can afford and that the housing shortage costs more than $140 billion per year in lost economic output. Middle-class employees can’t afford to live near jobs, causing stressful commutes, wasted hours, and climate-altering emissions. Homelessness, in vehicles or on the streets, is pervasive.

Governor-elect Gavin Newsom promised to create 3.5 million new housing units by 2025, a sensible goal to fill a pressing need. State Senator Scott Wiener of San Francisco may hold the key to helping the incoming governor fulfill his pledge.

Wiener previously introduced SB 827, a bold and controversial bill to overcome resistance to development by easing restrictions on housing density near transportation hubs. His bill died in committee in spring.

Now he’s back with an amended bill that adjusts some legislative provisions to blunt opposition while adding a compelling new one. The new bill, SB 50, would prevent localities from restricting higher-density housing within a half-mile of rail transit and within a quarter-mile of high-frequency bus lines. The new twist is this: The bill would similarly prevent restrictions near “job-rich” areas, including the gilded real-estate meccas of Silicon Valley.

Allowing the construction of four- and five-story housing near public transportation would produce more affordable housing while strengthening the case for robust public transit investment. To soften resistance from anti-gentrification forces, the bill would allow “sensitive communities” to delay implementation of the law for up to five years.

The new bill is a work in progress. It’s unclear, for example, how much discretion local planning boards would retain to shape the law to suit neighborhood preferences. Such an ambitious agenda is unlikely to succeed without a mechanism to accommodate local tastes.

Yet California needs virtually any housing it can get — luxury, middle-class or low-income. A study of San Francisco, where rents are stratospheric and homelessness is shockingly common, found that virtually the entire city would be subject to the bill’s high-density zoning.

In an old city renowned for its charming architecture, trepidation over new zoning rules is understandable; historic preservation shouldn’t be tossed aside. But one way or another, California’s cities and suburbs, and the vested interests that dominate them, are going to have to meet the demand for new and affordable housing.

For California to thrive, it must adequately house the nearly 40 million people who live there. For it to remain a global magnet, attracting a new generation of dreamers who envision new industries, Californians must make room for the future.

—Editors: Francis Wilkinson, Clive Crook.To contact the senior editor responsible for Bloomberg View’s editorials: David Shipley at [email protected].

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit

COPYRIGHT

© 2018 Bloomberg L.P