When Savanna was looking to snatch 80 Broad Street in Lower Manhattan early this year, it prepared for a lengthy siege.

The New York-based private equity firm knew that the office tower’s owner, a partnership of Swig Equities and Broadway Management, was in hot water. A $12 million mezzanine loan on the 417,000-sq.-ft. property had soured, and Cushman & Wakefield was shopping the defaulted first mortgage, which had more than $98 million in its principal still on the books.

The scenario was ripe for a cash-flush investor like Savanna to dig its heels into a debt position and then work from that foothold to increase its share to a partial or total ownership stake.

And there’s good reason that Savanna might have expected a long battle, not the least of which is the fact that private equity investors are still viewed with some skepticism as vulture investors. Remember, we’re talking about firms that that used to call their breed of investing “leveraged buyouts” but had to ditch that moniker after so many of the high-profile deals struck in the 1980s went sour.

Yet Savanna did not face a struggle. It negotiated simultaneously on several fronts to acquire the debt on the property, clear its liens and take over as owner.

Savanna obtained the first mortgage on 80 Broad Street for $66.3 million, a 33% discount from the $98.4 million the borrower still owed. It picked up the $12.5 million mezzanine loan for $1.6 million. All told, the property carried $266 of debt per sq. ft.

At that level, the private equity firm expects to generate juicy annual returns of 20% or more for its investors simply by performing needed maintenance and leasing the property at market rates. Current repairs include replacing the elevator and finishing out model offices that will be ready to show prospective tenants when the space re-launches in the first quarter next year.

Moreover, rather than lock the borrower out of the deal, Savanna retained the former owner to stay on and manage the building. “He knows the property better than anyone, and that gave him an additional incentive to work with us on the transfer of the deed,” says Nicholas Bienstock, a managing partner at Savanna, referring to Swig president Kent Swig. “To avoid a lengthy legal battle, we needed to make a deal that not only made sense for Savanna, but also for the borrower.”

The deal is emblematic of the role private equity players have come to play in the existing climate. Many have raised distressed funds for exactly this sort of situation. They aim to come in, buy an asset on the cheap from a troubled owner and turn around the property where many basic tasks, such as maintenance or marketing of vacant space, have fallen off. The strategy often benefits the former owner, the lender and the tenant. And it doesn’t hurt that the deals meet private equity investor’s elevated return goals—generally in excess of 15 percent.

“Sometimes they’re partnering with both the out-of-money equity holder and the lender at the same time, in effect being the white knight, bridging the gap and bringing the new capital to bring the asset to market,” says Steve Coyle, chief investment officer of Global Realty Partners at New York-based Cohen & Steers. “The new capital source is in control in most cases. That is the new paradigm for distress.”

Big spenders

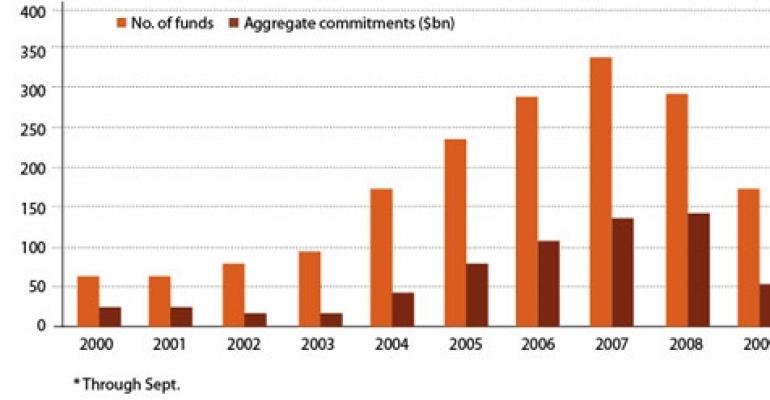

Private equity investors constitute a major force in commercial real estate today. Some 435 private equity funds are focused on commercial properties, targeting aggregate commitments of $138 billion, according to London-based research firm Preqin.

And fund raising is accelerating: 18 commercial real estate funds reached a close in the second quarter this year, collectively raising $11.2 billion. That’s up from $8.9 billion raised in the first quarter of 2011 and $7.1 billion in the fourth quarter of 2010, according to Preqin. Of the total from the second quarter, 10 funds and $8.6 billion were earmarked for North America.

Increasingly, those funds are earmarked for distressed opportunities. Overall, 22% of the capital raised in 2010 is allocated for some degree of investment in distressed assets, and the $21.6 billion collectively raised by those funds represents nearly half, or 48%, of aggregate capital raised in the sector.

That’s a marked change from a few years earlier—before the Great Recession and credit crisis. From 2000 through 2006, less than 3% of real estate private equity firm targeted distressed properties as potential acquisitions.

“Since the downturn of 2008, we’ve seen a surge of funds targeting these [distress] opportunities,” says Andrew Moylan, Preqin’s manager of real estate data. “It’s always been a part of the industry, but it was a niche area.”

Indeed, some of the biggest private equity deals that took place this year have involved distressed assets or took properties off the hands of overleveraged owners. In the biggest commercial real estate deal since 2007, for example, Blackstone Group L.P.’s Blackstone Real Estate Partners VI L.P. acquired Centro Properties Group US for $9.4 billion.

More recently, a separate fund acquired a another portfolio of shopping center assets from Equity One.

And unlike its last big commercial real estate gambit—the monster $39 billion acquisition of Equity Office Properties that arguably marked the peak of the cycle in early 2007—this one won’t be about flipping assets. Instead, Blackstone’s entry is allowing Centro to mount a comeback, focus on operations and improve the occupancies and incomes of its assets. The changes include a recent move by the company to rebrand as Brixmor Property Group.

Turnaround strategies

In part, private equity firms moved into distressed acquisitons because they are seeking returns higher than those available on other commercial real estate investing opportunities.

“Where private equity has had more success is by moving down the quality scale,” says Jim Sullivan, managing director of REIT research with Green Street Advisors, a Newport Beach, Calif.-based consulting and advisory firm. “They are buying a tent that’s a little less crowded.”

David J. Lynn, managing director with Clarion Partners, adds, “The idea is buy low, solve some problems with leasing, management, even some minor property issues, then wait until the economy improves and sell it. It’s a pretty opportune time of the cycle. It’s good to buy when there is a lot of fear.”

Brookfield Asset Management’s recapitalization of General Growth Properties in 2010 serves as a high-profile example of private equity coming to the rescue of a distressed owner. Brookfield, a publicly-traded global asset manager, directs six opportunistic property funds that are either nearly or fully invested, including the North American Opportunity Funds I & II and the $5.5 billion Real Estate Turnaround Protocol. The latter fund specifically targets distress, opportunity investments and debt. Brookfield recently launched an opportunistic fund targeting $4 billion for global real estate investment, as well as distress-oriented private equity fund targeting $1 billion.

Brookfield and its partners provided an equity injection of $2.625 billion that brought General Growth out of bankruptcy. In the end, existing General Growth shareholders retained ownership of more than a third of the company.

It is best to work constructively with all stakeholders in a distress situation, from owners to lenders and tenants, according to David Arthur, managing partner of North America real estate investments at Brookfield. “Building those relationships is often how you get transactions successfully completed,” says Arthur. “I would consider us to be in the white knight category and a constructive force in distress situations."

The right note

In addition to cash infusions into flagging companies and direct acquisitions of properties, another common tactic taken by private equity firms is purchasing notes from lenders.

Five of Savanna’s recent Manhattan office acquisitions began as note purchases and progressed to deed transfers. In many cases, a note purchase is the buyer’s only way to gain access to a particular property, according to Dan Fasulo, managing director with New York City-based research firm Real Capital Analytics (RCA).

“The frustration among many investors in this cycle has been that distressed assets aren’t for sale through your local broker,” Fasulo says. “You have to negotiate through several parties behind the scenes that are in several different parts of the capital stack, and that takes a level of expertise that’s not necessarily available at every investment shop."

Groups like Savanna also invest a lot of time and energy on researching properties in house in order to identify opportunities and close deals. “It’s incredible. People would kill for their record right now,” Fasulo says.

And that research has paid off. The fund manager has been the most active buyer of Manhattan office properties over the past two years, acquiring eight projects since the end of 2009 for a collective outlay exceeding $750 million, according to RCA.

While Savanna buys properties on a value-add basis, it sticks to high-quality projects that can be returned to profitability through repositioning.

“The kinds of buildings we are buying are, in a normal market, more typically core-plus assets, not opportunistic/value-added assets,” says Chris Schlank, one of two managing partners at Savanna. “The financial crisis and the resultant distress in capital stacks and within properties and partnerships have created an extraordinary opportunity to buy these kinds of assets in scale.”

Indeed, distress sales accounted for more than 20% of U.S. commercial property investment transactions in 22 of the past 24 months, according to a market update published by Moody’s Investors Service in late September. And with many mortgages originated in the peak year of 2007 coming due in 2012, investors can expect plenty of opportunities.

Another company that sometimes targets acquiring directly from lenders is the RADCO Cos., an Atlanta, Ga.-based firm whose subsidiary RADCO Investments LLC targets residential and hospitality assets for value-added and opportunistic returns.

This summer, the firm completed three transactions on multifamily properties, two direct acquisitions and a note, all from banks. It now has a turnaround strategy in place.

“We want to buy from banks because they’ve been our clients for a long time and we understand them and they are looking to dispose of assets right now,” says Norman Radow, founder and CEO of the firm. RADCO then revives the properties.

“You can’t underestimate the importance of strong management; the market responds to that,” he says. “Second, we have a moderate renovation plan to deal with deferred maintenance and to better take advantage of market dynamics.”

Still some skeptics

Despite the fact that private equity investors seem to play a benevolent role in the current cycle, skeptics remain.

Private equity players have taken some heat for deals that went bad. For example, many blame the trio of private equity investors that acquired retailer Mervyn’s for the firm’s eventual demise. The group split the firm in two — separating its retail operations from its real estate assets — and cashed out by selling Mervyn’s buildings and strangling the retailer.

One question going forward is how will firms exit the investments? When private equity firms were buying out REITs in the peak years, in many cases the investors quickly flipped the assets.

In today’s market, some observers believe private equity investors are also creating a dangerous situation by bidding up asset values too high in a few primary markets. The warning voices include Nori Gerardo Lietz, former chief real estate investment strategist at Partners Group and principal at Areté Capital, an independent San Francisco-based consultancy.

“They are the same vultures they were back in the early 1990s,” Lietz says. “They are only in it to make outsized returns.” She points to London, New York, Washington D.C., Paris and San Francisco as markets where private equity investors have driven down cap rates to dangerous lows.

Several recent sales in London transacted at cap rates of less than 4%, for example. “It’s hard for me to understand how you can see significant capital appreciation if the rents don’t go up,” Lietz says.

Private equity executives counter that with stagnant economic growth and uninspiring prospects for improvement for the next few years, secondary markets are simply too illiquid. That’s largely a reflection of available debt, which in secondary markets is difficult to obtain for any but the highest quality assets.

“The performance of secondary market investments is all about timing and basis,” says Mark Davidson, managing director of private equity funds at AEW Capital Management in Boston. “Right now the basis is high because pricing has been aggressive, and the timing is not good.”

Davidson and other investors contend that 24-hour gateway cities retain enough buyer demand, even in hard times, to provide an out when an owner needs to unload a property. In secondary markets, buyer interest can evaporate with a setback to a local industry or the larger economy. “If you miss the exit, you are now in a potential no-growth or downward fundamentals situation, and with no liquidity,” says Davidson.

Invaders as Liberators

Private equity funds scrounge for outsized returns in a low-yield world

One reason investors have poured capital into private equity real estate funds is the promise of meaty double-digit returns.

Private equity funds can use their cash and expertise to take on deals that are too complicated, and therefore too risky, for insurance companies, pension funds and other institutional investors, says Tom Fish, co-head and executive managing director of the real estate investment banking team at Jones Lang LaSalle.

“They have the ability to move fast and be creative in their deal structure,” says Fish, who works in the commercial real estate services firm’s Houston office. In return for taking on the risk of complicated transactions, many private equity funds expect to command returns in the teens or even higher.

But getting high returns can be a challeng when benchmark interest rates are at all-time lows. The 10-year Treasury yield, an important basis for long-term lending in commercial real estate, fell to 1.72% on Sept. 22, its lowest point ever. In response to these conditions, some private equity investors started looking for potential acquisitions beyond the relative safety of fully leased, stabilized assets in New York and Washington, D.C.

“They certainly have to go further out on the risk curve to get the yields they’re looking for,” says Fish. “They’re beginning to expand into other, secondary markets that they didn’t do a year before, markets like Florida or maybe Austin. Or maybe they’re willing to go down to a product type of a lesser quality because the yields might be better on that.”

Steve Roberts, senior managing director in the New York office of Grubb & Ellis, says private equity investors will be forced to take on more risk if they hope to make returns in the teens or higher. For some, that will mean investing in core assets in secondary markets. Others will stick to top tier markets but take on value-add projects or riskier positions in deals, perhaps as mezzanine investors. ”To get a 14% return, you have to take on more risk than somebody getting a 7% return.”

Yet economic uncertainty is pushing investors in the other direction. In light of the sovereign debt crisis and a flat U.S. jobs report in August, some funds might retreat to the relative safety of gateway cities, predicts Bob Plumb, managing director and head of direct investment acquisitions at AEW Capital Management in Boston.

“The whole world has changed now,” says Plumb, reflecting on the deteriorating economic outlook since early June. “For the balance of the year, people are going to be pulling in their horns and are going back into the core markets.”

– Matt Hudgins