The U.S. housing market has been declining since the expiration of the tax credit last spring, although recent data show some signs of leveling off. Helped by the 2011 spring selling season, the April S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices dipped 0.1% month-over-month, the smallest decline since July 2010.

Nonetheless, U.S. home prices have declined by approximately 30% on average since peaking in the summer of 2006. As both current and potential homeowners consider their housing options, we believe that continued price declines and a slow recovery in home prices are reshaping the economics of the “rent or buy” question.

With housing affordability near its all-time high, does it still make sense to rent? Here we compare the costs of renting versus owning in the top 49 markets across the country.

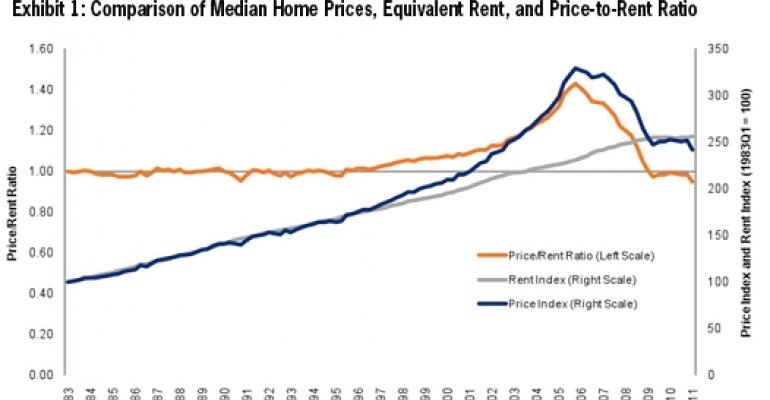

The price-to-rent ratio is one of the most common metrics used in assessing the health of housing markets. Historic data from 1983 through 1998 show a steady relationship between median home prices and rents at the national level [Exhibit 1].

Starting in 2000, rent growth did not keep pace with the steep home price appreciation, pushing the price-to-rent ratio well above the historic average. Many market observers have identified the dislocation between prices and rents as both an indicator of the housing bubble and as a tool for helping to understand the relative affordability of these two housing options.

Home prices have been declining since 2006, forcing the price-to-rent ratio to revert to its long-term average. As of the first quarter of 2011, the price-to-rent ratio is slightly below 1.0, suggesting that on the national level renting is essentially the same as buying economically, although the trend seems to be tilting toward buying going forward [Exhibit 1].

Although the price-to-rent ratio is a simple and effective comparison of the costs of buying and renting, it does not take into account the full range of economic considerations associated with the two housing options.

For example, many potential home buyers often anticipate tax savings and future price appreciation in order to offset higher purchase costs. We developed a framework that incorporates a variety of housing and market data in order to understand the total economic costs and benefits associated with renting and buying.

The main drivers in our model include current median home prices and effective rents, mortgage rates, insurance costs, maintenance costs, taxes, and opportunity costs of committed capital such as down payment and closing costs. We also account for tax savings (mortgage-interest and property taxes), and for the expected change in both home prices and rents over a four-year forecast period [Exhibit 2].

We analyzed costs of renting versus buying over a four-year forecast period (from year-end 2010 to year-end 2014) and use the premium/discount ratio of costs to own over costs to rent to compare 49 of the largest metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs).

A value of 1.0 indicates that the cost to rent is equal to the cost to own. A value greater than 1.0 indicates home ownership premium (the cost to buy is more expensive than the cost to rent), while a value below 1.0 indicates home ownership discount (the cost to buy is less expensive).

Exhibit 3 illustrates the markets by categories in terms of the comparative cost to buy vs. rent. Among the 49 largest markets, 41 show an ownership premium and favor renting, while only eight markets exhibit an ownership discount and support buying.

Many markets that show large ownership premiums, such as San Jose, New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., are currently experiencing robust rental growth, suggesting that households make rational renting or owning decisions greatly based on economics.

Home price appreciation or depreciation is the most influential factor in our analysis. In periods when home prices are rising, the ability to sell a home for a premium to the purchase price at the end of the hold period often overshadows the increased costs of ownership relative to renting during the hold period.

Nonetheless, given our current forecasts for home prices, which call for continued price declines in the near term and a slow rate of appreciation once the market hits bottom, price appreciation is expected to have a marginal or even negative impact on the overall costs to buy in many metro areas.

Markets that are expected to record the slowest average rate of home price appreciation during the forecast period also are among the markets with the highest costs to buy relative to renting.

For example, despite experiencing significant declines in home prices, Miami is still considered more affordable to rent in our analysis. We estimate that the cost to buy a median-priced home in Miami over the four-year period is 1.67 times the cost to rent.

The key reason is that Miami home prices are forecast to continue to fall over the next two years. Conversely, even with expensive home prices, Seattle has a ratio of 0.97 and is rated as a market where it is more economical to own primarily because home prices locally are expected to appreciate substantially over the next few years.

Of course, households make housing decisions based on a wide variety of factors, including household formation, job growth, consumer confidence, and the psychological and social benefits of homeownership, which extend beyond the considerations analyzed here.

Other factors that we believe exert salient, but less significant, influence on the outcome of the rent versus buy calculation include mortgage interest rates and the rate of growth for apartment rents.

Our analysis suggests that, from a purely economic standpoint, renting is a more attractive option for a growing number of households in most markets in the near term.

We believe that those markets with the highest cost to buy relative to rent are more attractive for owners or developers of rental products, as they may face less competition from the for-sale market.

We also believe that the potential for rising interest rates along with stricter lending standards and higher down payment requirements may further discourage buying.

David Lynn is a managing director, generalist portfolio manager and head of investment strategy for Clarion Partners in New York.